After a mere seventeen days' fall campaign proceeding from Harfleur (which had taken over a month's time to besiege, and required another two weeks' rest before the army was prepared to march onward from there) for some 260 miles through the north and west of France, some 6000 to 9000 (out of an original force of 12,000) tired, battle-weary, and raggedy English soldiers - overwhelmingly longbow archers - in the army of their young king, Henry V, found their last few days' march to Calais, which meant passage back home to England, blocked by a fresh French army of between 12,000 and 36,000 men, led by Charles I, Constable of France, and right-hand deputy to France's King Charles VI. Who promptly were not only soundly thrashed by the small English army (what would now be about a brigade), but slaughtered there by them, in a small valley between the towns of Tramecourt and Agincourt, on Wednesday, October 25, 1415 (falling on the same day of the week as it does this year).

King Henry had held his force to silence the night before the battle, telling his men he would rather die with them than be captured and ransomed (the usual fate of a vanquished leader of such stature), and advising them that the French had boasted that his archers would have their two right fingers amputated (and thus never be able to draw a longbow again) should they be captured in the fighting.

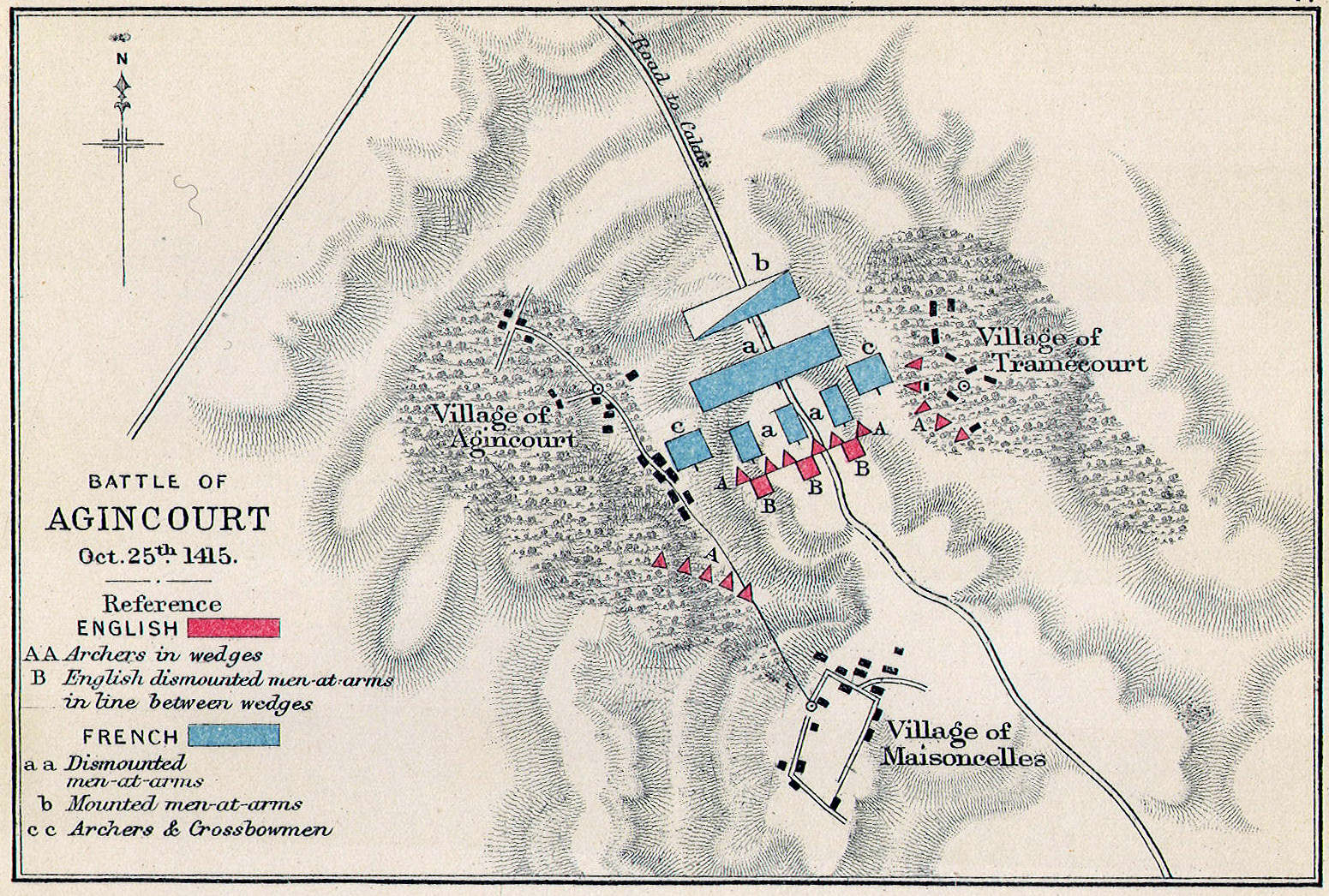

After three hours, which only let the French gain reinforcements, Henry reluctantly closed the 300 yard distance between the armies, leading the French to charge him as well. The main point of battle was a gap about 750 yards across, covered by 7000 English and Welsh archers, through which tens of thousands of French knights and infantry men-at-arms all had to pour through to get at the pitiably few 1500 English men-at-arms in the middle of front of the opposing line.

The gap, surrounded by dense woods on both sides, coupled with the knee-deep mud from fresh rains, and the pressure of so many French troops trying to get to so few English, made the field a shooting gallery for the English bowmen. As the front ranks fell, those behind stumbled forward, and were killed by fresh volleys, and the heavily-armored knights and men at arms were trodden, hardly able to arise once downed, and killed by arrows, maces, and knives to the throat, as fresh victims landed on top of them. The muddy fields themselves were such an obstacle that some of the French were said to have drowned in their helmets, unable to extricate themselves and regain footing.

All the while, English arrows, deadly even through most plate armor to 200 yards and accurately fired at three times that range in volleys, and fired by the archers behind a protective palisade of spikes, poured into the ranks arriving from the rear. Those archers out of arrows, lightly armored, charged into the melee and met the struggling French, hacking at them with swords, axes, knives, and the mallets they'd used to pound the palisade spikes into the ground. The combat was the most brutal sort of hand-to-hand imaginable amidst the mud and slaughtered hordes, in which even the English king took part, receiving blows and striking down enemies at the center of the line.

In three hours' fighting (condensed to six minutes and a few volleys of arrows above), the English had captured so many French beyond those slaughtered, the order was given to kill the lower-ranking captives as well, mainly to terrorize the remaining and still numerically superior French reserves into retiring, but also because the French taken prisoner outnumbered the remaining English army combatants.

The French retreated, after losing between 4000 and 12,000 men, including the Constable of France, the Admiral of France, the Marshall of France, the Master of Crossbowmen, and the Dauphin, head of the royal household, as well as 3 dukes (ranking immediately after a prince), 6 counts, an archbishop, and various other nobility. In contrast to English casualties of a few hundred, including the Duke of York and the Earl of Suffolk.

The French losses were primarily to the Armagnac faction, then ruling France, which led immediately to the out-of-power Burgundian French to break their truce with the Armagnac, assemble their own armies, and march on Paris. Henry decamped to Calais and returned to England, entering London as a conquering hero.

The archers, having survived and triumphed, did not lose their fingers as threatened by the French, and are said to have saluted them by raising the pair, giving birth to the "V" for victory sign unto the present day,

and a close cousin of the form wherein only one finger is used in saluting one's enemy.

Henry gained Catherine of France as a wife, who bore his sole heir, and he died mere months after that birth on campaign in France seven years later, at the age of only 36, as heir apparent of France. When Charles VI of France died two months later, his son disputed the claim of the infant English king to reign over France, and Henry VI being nowhere as good a general as his father had been, and occasionally barking mad, managed to lose all English possessions in France save Calais by 1453, leading directly to English civil war in the Wars of the Roses, which saw his Lancastrian side defeated by Edward IV and the Yorkists, and himself imprisoned in the Tower of London, and dying there (most likely murdered on Edward's orders) to end the Lancastrian line of English kings.

Proving, exactly as in the closing line of the movie Patton, that "all glory is fleeting."

6 comments:

The "V" for victory sign also is used the same way the middle finger is over here.

I always thought it more romantic the "V" was a simple "fuck you" to the frogs.

Ned2

When I arrived in Australia years ago, I hit a roundabout for the first time. No idea of the rules so drove around the thing a few times getting a few "peace" signs in the process. Thought at the time the Aussies were nice and friendly as I'd have flipped off anybody driving that badly in front of me.

Thanks for posting this topic about Agincourt.

Fascinating battle.

Great movie and play.

Thsnks for these history posts. Your picking up Hognose's torch is really wonderful. I appreciate the work you've put in. Thanks.

YW. I had a week's time or so when I realized it was coming up, so...

As to "picking up Hognose's torch", I'm pretty sure this all is just a shadow in comparison. But I'm a sucker for good history. Multiple events that all line up on one day was too good to pass up.

The Battle of Agincourt.

The bloodiest battle of the Medival Age.

Full documentary.

https://youtu.be/KYH40k_9gMA

Post a Comment